“Indeed, Islam began as something strange, and it will return to being strange just as it began. so glad tidings of paradise be for the strangers, the ones who are righteous and are guided by Allah.” ~ Prophet Muhammad, salla Allahu alayhi wa sallam.

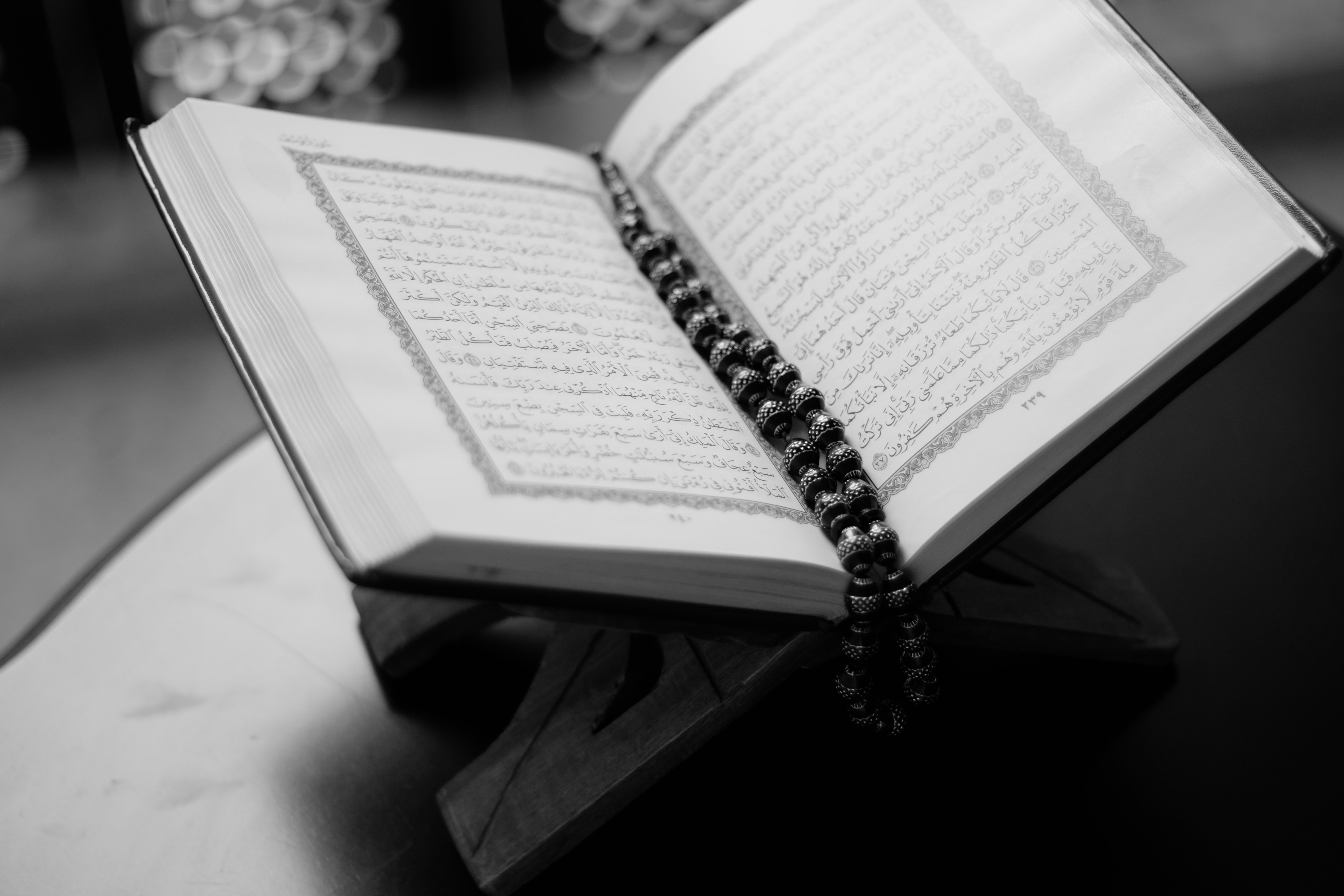

When I started writing this novel, I set in my heart that I wanted to write an honest, heartfelt depiction of David’s Islamic experience. His journey into and out of the faith, explored against September 11, 2001, the greater War on Terror, and the existential shock that has pulsated through the Middle East since. I wanted to delve deep into what it means to be a Muslim, to love Allah with one’s whole being, to live to the rhythms of Islam. To embrace an Islamic and Arab identity.

I hope my attempt has succeeded, at least in part.

One of the most frequent questions I am asked by editors and proofers, following Whisper, is, “Are you Muslim?”

At the time of this writing, no, I am not. However, to dive deep into the soul of Islam and attempt to portray the faith with any shred of justice, I felt it was only appropriate to go to the very center of Islamic studies.

To that end, I enrolled in an Islamic seminary as a visiting student, and I still am a student.

The imams and scholars have warmly welcomed me as a seeker, opening their arms, their hearts, and their minds to my journey of understanding. I like to think, in some ways, we have helped open each other’s minds in certain areas.

I am queer, gay, and (loudly) out. My husband and I do not hide our relationship. We take what comes with that, all the ups and downs. In Islam, homosexuality as a personal identity is—at present—considered haraam, or forbidden, by the majority scholars. I stress “as a personal identity” because that is the crux of many current discussions about homosexuality in Islam.

The Islamic faith, as practiced in many countries, bifurcates the genders and enforces strict gender segregation. A homosocial culture for men is thus created, where men find their emotional, social, and oftentimes physical needs satisfied by other men.

This duality can be hard for Westerners to grasp. To study homosexual behavior and homosexual identity in strictly Islamic societies, it’s necessary to put aside all understandings of what it means to be gay in the West, or to identify as LGBT as a Westerner.

Homosexual behavior—men having sex with men—does not lead directly to a gay identity 100% of the time. This is true everywhere. Homosexual behavior occurs often in environments where there are no females, and, as human beings, men seek physical and emotional connections with other men. Prison is a classic example of such behavior. Some male boarding schools, and some military units as well, foster this kind of homosocial behavior.

In devoutly Islamic societies, it can be common for men to have sex with other men and NOT label their behavior as part of a homosexual identity, or of themselves as gay. For readers of my Executive Office series, Uncle Abdul, the fictional Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia and the uncle to my character, Faisal al-Saud, remarks on how ‘it is not unheard of’ for men to slake their lust with other men. In Saudi Arabia, the Gulf countries, Northern Africa, Pakistan, and even Afghanistan, sex between men is relatively common.

However, these men are expected to marry wives, father children, and hold on to their straight identity. (Being “gay” is not even a consideration.) These men are not “gay”, in the sense that they identify as a man who desires and loves other men to the exclusion of women. To them, and to the society they inhabit, they were only expressing their physical desires.

In Kabul, it was once said, “men are for sex and women are for babies.” The Taliban used to have pool parties where they ogled each other’s bodies and figures beneath their swim suits, and many Taliban members would then retreat to have sex with each other—all men. In the West, we’d most closely link these behaviors to the idea of “helping a buddy out” sexually. Something done, but not emotionally meaningful.

The cognitive dissonance, and the current struggle in present ideological Islam, is when a Muslim man wants to grasp a gay identity and wants to live their life as a gay man (much like Faisal chooses to do).

There is wide variance in how repressive an Islamic country is to a man claiming their gay identity. Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and Egypt are three countries where owning a gay identity and wanting to live openly as a gay man can get you arrested and/or killed. Lebanon and Bahrain are two of the most open countries; in Bahrain, being gay is legally allowed and protected. In Lebanon, the courts have ruled that Article 534, which prohibits people from having sexual relations that “contradict the laws of nature” cannot be used against LGBT persons. Thus, in Lebanon, being gay is de facto legal as well, by court precedent.

So, am I a Muslim today? No.

Am I an Islamic seminarian? Yes.

Could I, one day, see myself as a Muslim? Yes, to the extent that, through my studies, I now nurture a burning desire to be a voice for peace, love, and acceptance within the Islamic world.

Muslims for Progressive Values is a small but growing voice in progressive Islam. With chapters around the world, MPV is a “human rights organization that embodies and advocates for the traditional Quranic values of social justice [bringing together] an understanding that informs our positions on women’s rights, LGBTQI inclusion, freedom of expression and freedom of and from belief.” (www.mpvusa.org) MPV’s vision states: “[We] envision a future where Islam is understood as a source of dignity, justice, compassion and love for all humanity and the world.”

What does being a Muslim mean to me?

To me, to be a Muslim is to be at peace with the universe. To have internally surrendered to Allah, to be in a constant state of surrender to Allah, to His love and compassion, and to the universe. To be in harmony with what Is.

To be in a state of Islam is to hold the faith of Allah in the center of your soul.

Today, Islam is experiencing a revolution, one as existential as the Reformation was to Christianity. Muslims and non-Muslims are struggling to answer questions about Islamic identity, the intersection of Muslim faith, politics, and society, and how to reconcile Islam’s past, present, and future. The question of gay identity in Islam, and LGBTQ acceptance, is but one of those issues Islam must address and reconcile. I firmly believe that there is acceptance within the faith for all human beings, no matter their race, ethnicity, color, creed, gender, or sexual preference. It is my firm belief that there is a welcoming place in Islam for all LGBT peoples.

We just need to get there.

Selected text from Author’s Notes of Whisper